Hello Friends,

This article will discuss the life of Marie Skłodowska Curie: her life is an example of dedication to science based on altruism, personal growth, and tenacity.

She holds a very special place in our household. She inspires us everyday especially her quote,“Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less”

A little secret: we chant this quote every time we overcome any obstacle or solve a problem!! :)

Women of Firsts

There is a lot to learn from her life. Marie Curie advanced not only science, but also women's place in the scientific community. She was a woman of firsts. She was one of the first women to earn a PhD. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win two of them, and the first of only two people to win a Nobel prize in two different fields (chemistry and physics, in her case). She coined the term "radioactivity," discovered two elements, polonium and radium and became the first female professor at the University of Paris. She was also the first to include lab work in the institute’s physics curriculum.

Being the first woman to break through so many barriers in a totally male-dominated science makes her an emblematic figure in the fight for equal opportunities and human rights.

She said, “You cannot hope to build a better world without improving the individuals. To that end, each of us must work for his own improvement and, at the same time, share a general responsibility for all humanity, our particular duty being to aid those to whom we think we can be most useful”.

What do you do to self-improve and what are your ideas which can help improve humanity in general ?

In this section we will cover the major highlights of her life and the life lessons we can all learn. This is a long read article; however you can skim through the important highlights by just reading the bulleted and italicised portion. Happy Reading!

Tragic Early Childhood [1867-1882]

On 7 November 1867, Maria Skłodowska was born in Warsaw, Poland, she was the youngest of five children. Her childhood nickname was Manya. Her parents were poor. Both her parents were school teachers and valued education, and so she began her education early.

At tender age of 10, she lost her sister to typhus and two years later her mother died from tuberculosis. Curie found solace in her studies and overcame her grief. "Temporarily crippled with grief, the young girl threw herself into her studies, remembering how her mother had told her that knowledge was more valuable than material possessions" - Deborah Huso.

She was a remarkable child with incredible love for learning, especially both literature and Maths. She was notable for her diligent work ethic, neglecting even food and sleep to study. During that time, Warsaw was under Russian occupation and women were not allowed to study. Her father, being a science teacher taught her physics and maths and encouraged her curiosity to seek formal education from secret school called the “Floating University”-a set of underground, informal classes held in secret, its locale changed regularly to avoid detection by the Russians. Under the dictatorship regime, resources and freedom were scarce.

Under these circumstances life was hard but little Marie overcame it with her belief that knowledge and education were attributes of life that couldn't be taken away by anyone.

I was taught that the way of progress was neither swift nor easy - Marie Curie.

Several impediment to Education [1882-1893]

She graduated high school, at age 15, with gold medal but was not allowed to study in University. Her father was poor and could not support for her higher education and she had to go to work at a young age as a tutor, postponing the continuance of her own education. But she never lost her passion for knowledge. Determined to continue her education, she worked out a deal with her sister. She decided to work as a governess to financially support her elder sister, Bronia, to be a doctor and in return sister will help Marie to go to college.

So following the pact, at age 18, she started working as a governess, and in her spare time she started studying physics and chemistry on her own and, by correspondence with her father, took an advanced math course.

As per the agreement Bronia returned the favour. At the age of 24, she offered her to come to Paris, she grasped the opportunity. In the fall of 1891, she enrolled in Sorbonne University to study Physics and Mathematical Sciences. During her years in Paris she changed the spelling of her name to the French version, Marie.

She studied fervently, rationed her intake of food, subsisted almost entirely on bread, butter, and tea. Science thrilled her, and she earned a degree in physics in 1893 and another in mathematics the following year.

This is how she describes her time at Sorbonne, “All my mind was centered on my studies, which, especially at the beginning, were difficult. In fact, I was insufficiently prepared to follow the physical science course at the Sorbonne, for, despite all my efforts, I had not succeeded in acquiring in Poland a preparation as complete as that of the French students following the same course.”

Despite lack of fluency in technical French and inadequate formal training in math and science, within three years Marie completed, with distinction, the equivalent of master’s degrees in both physics and math. There she also obtained her Licenciateships in Physics and the Mathematical Sciences and became the first woman to be employed as a professor at the University of Paris.

Roadblocks, challenges, impediments are immutable part of every person’s life journey. However some use it as stepping stone and some bury themselves in grief when faced with the impediments. Whenever you face them in life remember Marie Curie’s life challenges and her incessant desire to pursue education against all odds. Also it is noteworthy to mention famous life lesson from Stoic philosopher, Marcus Aurelius - “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way”

Marriage of Like Minds [1893-1897]

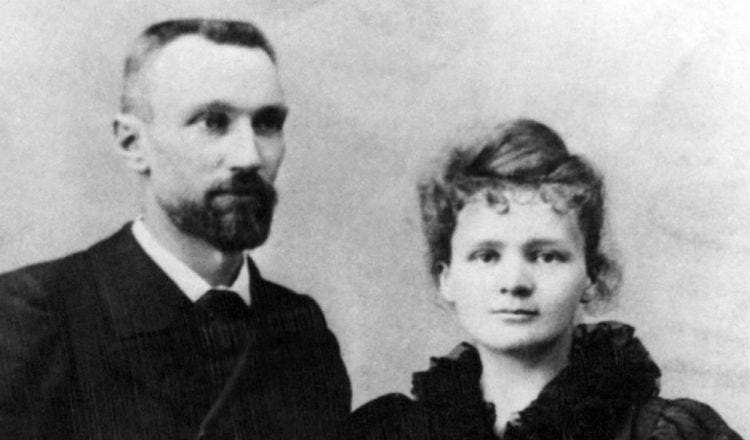

She was then commissioned to work on a project, to relate the magnetic properties of several steels to their chemical compositions by Society for the Encouragement of National Industry. To begin her research, she has to first secure a lab space. During this search, she met Pierre Curie, a 35-year-old physicist at a French technical college who had been studying crystals and magnetism. He co-discovered the piezoelectric effect and invented a sensitive scientific balance named in his honor.

Both were smitten in presence of other. Marie recalled the first meeting, “I was struck by the open expression of his face and by the slight suggestion of detachment in his whole attitude. His speech, rather slow and deliberate, his simplicity, and his smile, at once grave and youthful, inspired confidence.”

Pierre was taken by Marie’s uncommon intellect and drive, and one year after meeting her, he proposed to her. “It would...be a beautiful thing,” he wrote, “to pass through life together hypnotized in our dreams: your dream for your country; our dream for humanity; our dream for science.”

On 26 July 1895 Pierre and Marie had a civil wedding ceremony in Sceaux. Instead of a bridal gown, Marie wore a dark blue dress. She explained, “I have no dress except the one I wear every day. If you are going to be kind enough to give me one, please let it be practical and dark so that I can put it on afterwards to go to the laboratory.”

For their honeymoon, the Curies took a bicycle tour around the French countryside. They had two beautiful and talented daughters, Irène and Ève. Their elder daughter, Irène Joliot-Curie followed her parents footsteps and was a Nobel Prize awardee. Ève chose to be a French and American writer, journalist and pianist. She authored her mother's biography Madame Curie.

First Nobel together [1897-1903]

They came together over their research into magnetism, but Marie was intrigued by the remarkable discovery done by Henri Becquerel in 1896. He had shown that the rays emitted from Uranium were able to pass through solid matter, fog and photographic film and caused air to conduct electricity. Curies then completely focussed their research on radiation. Together they studied uranium ore pitchblende. Pierre adapted the Curie electrometer to enable Marie to measure the faint currents given off by the rays. By 1898, they reported that the pitchblende contained traces of some unknown radioactive component that was far more radioactive than uranium. In 1902, the pair isolated the chloride salts and added two new elements in the periodic table; the first they named polonium after Marie's native country, Poland and the second was named radium from its intense radioactivity.

Pierre, meanwhile, discovered that radium emits heat spontaneously and that its emissions can damage living tissue, a discovery that inaugurated the use of radioactive treatments for cancer and other ailments.

Marie Curie says that, “When radium was discovered, no one knew that it would prove useful in hospitals. The work was one of pure science. And this is a proof that scientific work must not be considered from the point of view of the direct usefulness of it.”

In June 1903, Marie defended her thesis, “Research on Radioactive Substances,” which, her examiners claimed, contributed more to scientific knowledge than any previous thesis ever published. Six months later, Becquerel, Pierre Curie and Marie Curie were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics “for their research on the radiation phenomena discovered by Becquerel.” Curies, due to ill health, now attributed to their promiscuity with radioactive elements, were not able to receive the award in person.

Undermining Marie’s scientific contribution

At first, Marie was not included in the Nobel prize nomination. But when Pierre found out he complained and Marie’s name was added.

At the awards ceremony, the president of the Swedish Academy, which administered the prize, quoted the Bible in his remarks about the Curies’ research: “It is not good that man should be alone, I will make a helpmeet for him.” Her scientific contribution was not well credited, such an opinion was widely held, judging from published and unpublished comments by other scientists and observers.

Even after winning the Nobel Prize, Pierre was promoted to full professorship but Marie was not promoted. Pierre honoured Marie as a scientist, he decides to assist her by hiring more assistants and made Marie the official head of the laboratory. This helped her to freely conduct experiments and for the first time, be paid for it.

They truly were power couple of that era. They had the most successful scientific collaboration between husband and wife in the history of Science.

Science has great beauty [1903-1906]

Today, we are aware of the potential harmful effects of radioactive radiations on health. But when Curies were working with radioactive elements, little was concretely understood about both short and long-term effects of radiation on health.

Unaware of the potential hazards to health, they immersed themselves in the daunting and elaborate process of extracting tiny quantities of radium from radioactive pitchblende on large scale. The strenuous process involved several steps – grinding, dissolving, filtering, precipitating, collecting, redissolving, crystallising and recrystallising. Since their regular lab weren't big enough to accommodate the process, so they moved their work into an old shed behind the school where Pierre worked. After the famed German chemist Wilhelm Ostwald visited the Curies' shed to see the place where radium was discovered, he described it as being "a cross between a stable and a potato shed, and if I had not seen the worktable and items of chemical apparatus, I would have thought that I was been played a practical joke."

They were amazed by the glow of Radium, they used to keep a sample at home next to bed and use it as nightlight. They used to keep bottles of polonium and radium in their pockets. In her autobiography, she describes "One of our joys was to go into our workroom at night; we then perceived on all sides the feebly luminous silhouettes of the bottles of capsules containing our products. It was really a lovely sight and one always new to us. The glowing tubes looked like faint, fairy lights."

Curies notebooks, her clothing, her furniture, pretty much everything surviving from her Parisian suburban house, is radioactive, and will be for 1,500 years or more. As we know now, the most common isotope of radium, Radium-226, has a half life of 1,601 years.

After regularly handling radioactive samples, both were said to have had developed unsteady hands, as well as cracked and scarred fingers. Pierre was suffering from chronic fatigue and pain when he died in a tragic road accident in 1906. He was hit by a horse-drawn vehicle and fell under the wheels.

Second Nobel after Pierre’s death [1906-1911]

Pierre’s death left Marie devastated but she was determined to honour him in any way she could. She said, “One never notices what has been done; one can only see what remains to be done”.

Her indomitable spirit kept her to continue their research. Instead of accepting a widow’s pension, she took her husband’s place as Professor of General Physics at the Sorbonne, becoming the first woman Professor.

She wrote a diary during this time, addressed to her late husband, about continuing their research. “I am working in the laboratory all day long, it is all I can do: I am better off there than anywhere else,” she wrote.

Curie’s nomination to the French Academy of Sciences was rejected, and many suspected that biases against her gender and immigrant roots were to blame. Among the false rumors the right-wing press spread about Curie was that she was Jewish, not truly French, and thus undeserving of a seat in the French Academy.

In 1911, Marie won her second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, "in recognition of her services to the advancement of chemistry by the discovery of the elements radium and polonium, by the isolation of radium and the study of the nature and compounds of this remarkable element".

Though she had just been awarded a second Nobel Prize, the nominating committee now sought to discourage Curie from traveling to Stockholm to accept it so as to avoid a scandal. Scandal was her love affair with Paul Langevin, a brilliant fellow physicist and former pupil of Pierre Curie. With her personal and professional life in disarray, she sank into a deep depression and retreated (as best she could) from the public eye.

Around this time, Curie received a letter from Albert Einstein in which he described his admiration for her, as well as offered his heart-felt advice on how to handle the events as they unfolded. “I am impelled to tell you how much I have come to admire your intellect, your drive, and your honesty,” he wrote, “and that I consider myself lucky to have made your personal acquaintance . . .” As for the frenzy of newspaper articles attacking her, Einstein encouraged Curie “to simply not read that hogwash, but rather leave it to the reptile for whom it has been fabricated.” Soon enough, she recovered, reemerged and, despite the discouragement, courageously went to Stockholm to accept her second Nobel Prize.

She responded to critics by saying, “I believe there is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of private life.”

In her 1923 memoir, Marie explained that her measurements suggested a revolutionary hypothesis: “My experiments proved that the radiation of uranium compounds ... is an atomic property of the element uranium ... and depends neither on conditions of chemical combination, nor on external circumstances, such as light and temperature.” Curie’s hypothesis revised the scientific understanding of matter at its most elemental level and it paved the way for Atomic Physics.

In her Nobel Prize acceptance speech at Stockholm she paid tribute to her husband and scientific collaborator. She also spelled out that her work was independent from his and describing the discoveries she had made after his death.

She was a woman of action, her Nobel Prize winning work after Pierre’s death renounced her credibility in the male dominated scientific world.

Major hero of World War I [1911-1934]

At the end of 1911, Curie became very ill. The potential damaging effects of radiation were showing up on her health, she had an operation to remove lesions from her uterus and kidney. After long recovery period, in 1913, she opened and headed a new research facility in Warsaw.

As she was setting up a second institute, in Paris, World War I broke out. Rather than flee the turmoil, she decided to join in the fight. But foremost she planned to hide all the Radium she had isolated in laboratory to a safe place to avoid confiscation from Germans.

When French Government called out to citizens for Gold for the war effort, Marie offered her two Nobel Prize Gold medals. However, bank officials refused to melt them down, so she donated her prize money to purchase war bonds instead.

She was appointed the Director of the Red Cross Radiology Service. Determined to put x-ray technology to use in military hospitals, she persuaded her wealthy friends to fund her idea for a mobile x-ray machine. Ultimately 20 "petite Curies," as the x-ray machines were called, were built for the war, they were vans equipped with a generator, hospital bed, and x-ray equipment. Marie, assisted by her 17-year daughter, Irène, and several other volunteers examined the wounded soldiers on battlefield to help physicians locate bullets, shrapnel, and broken bones.

But to Marie's astonishment, the concept of X-rays on the front wasn't just foreign—it was actively fought against by doctors who felt that new-fangled radiology had no place at the front. Ignoring the protest of the French army's medical higher-ups, Marie drove to the Battle of the Marne, intent on proving her point. The x-ray machine worked beautifully and helped save lives of many.

Not completely aware of the dangers of overexposure to x-rays, the mother-daughter team took inadequate precautions, wearing cloth gloves, occasionally separating themselves from the equipment with small metal screens, and avoiding direct beams whenever possible.

Curie subsequently trained about 150 female radiological assistants at the Radium Institute. Curie also established a military radiotherapy service. After the war’s end in November 1918, Curie also offered radiology courses to U.S. soldiers through the Radium Institute.

Death of a Science Warrior [1934]

Over the final 14 years of her life, Curie’s health rapidly declined. On July 4, 1934, Curie died in a sanatorium in Switzerland from “an aplastic pernicious anemia,” probably caused by “a long accumulation of radiations.” All her life Curie refused to acknowledge a possible link between her health and radiation exposure.

For more than 60 years she lay in a cemetery alongside Pierre’s remains. In 1995, however, their remains were transferred to the Panthéon, France’s national mausoleum. Curie thus became the first woman whose own achievements merited her burial alongside France’s most important men.

At the time of the transfer, researchers analyzed the radium levels in her original coffin. They concluded that the levels were too low to account for her death. The current theory, therefore, is that Curie died not from the radium she handled with bare hands—and often sucked up with pipettes to transfer from container to container—but rather from exposure to X-rays during the war.

Marie Curie was a multifaceted woman of uncommon intensity, intelligence and will—a woman of courage, conviction and also contradictions. She is one of the 20th century’s most important scientists, who was, at the same time, unmistakably, reassuringly human.

I’ll leave you all to ponder upon another Marie Curie’s inspiring quote:

Life is not easy for any of us. But what of that? We must have perseverance and above all, confidence in ourselves. We must believe that we are gifted for something and that this thing must be attained.

I have a simple request to make - Please share this article with one person and help spread knowledge and passion for Science!